Peter Bösenberg, Dirk Eicken, Luis Gordillo, Alex Hanimann, Susanne Kutter, Axel Lieber, Christopher Muller, Björn Siebert, Markus Willeke

March 6 – April 29, 2017

The word dislocation refers to a defect in a molecular structure. This can mean a fault in a lattice structure or the intrusion of an incorrect row into an established order. One can expand the use of the term and ask whether it might also apply to things—or even to people and their behavior. There are natural contexts for objects or ways of human life. We speak of something belonging here or there, to its natural place. In doing so, we assume that we, as humans, are capable—through perception—of distinguishing between such different contexts, places, and orders, and of assigning things to them clearly.

These natural contexts or places are increasingly being disrupted; orders are thrown into confusion, foreign objects or people intrude into existing systems or are expelled from them. When orders or natural environments are lost—for things or people—familiarities collapse. It becomes difficult to attribute specific properties to these things or people, and it becomes ever harder to form stable expectations.

When things or people are uprooted, they become something else—we no longer recognize them. And as our world becomes more densely layered and contexts increasingly overlap, it becomes harder to determine what is real and what belongs to newly created artificial spheres—what is fiction or dream, and how something’s relation to reality can still be discerned.

With such a rise in uncertainty, one may ask whether orders are still possible—whether clarity and orientation are still attainable for the major, essential domains of our lives. One may view this development positively, as a sign of increasing individualization of the world—or one may lament or criticize the fact that there no longer seem to be natural places suited to life. The latter attitude has led to a strong ecological movement and to a renewed turn toward religion. The word ecology is rooted in the idea of a “science of the proper management of the household” (oikos), which implies a vision of life being properly embedded in its environment.

Where doubt grows about what is truly meaningful—about what might constitute the core of a well-lived life—and where identification with the natural places of life no longer takes place, we witness counter-movements that offer irrational new points of reference, developing a form of magic or sacredness that may at first seem absurd to us.

In our 2017 exhibition Dislocation, we bring together a wide range of works that deal with uprooting, alienation, and destruction—but equally with novel forms of idolization or sacralization. The works differ greatly in their media and aesthetic qualities. Some appear factual, others more sensually opulent, and still others almost absurd. But precisely because these are artworks, one should not be misled by surface appearances. Artworks consciously incorporate their external form into their conceptual framework and often use it to serve opposing purposes.

Peter Bösenberg explores the peripheral zones of our cities, seeking out the interpenetration and overlapping of different orders. Living, storing, managing, producing, repairing, transporting—all collide here. Buildings, vehicles, streets, squares, walls, and fences spread out, fill with people, and are connected by empty lots and wastelands. These marginal zones do not follow natural or organically grown orders. Change occurs here abruptly and violently. Dislocation, unwanted, becomes the norm. The anarchy between the different objects is further shaped by general mobility and media saturation, the latter appearing unfiltered in the form of large billboards—against which the omnipresent graffiti seem to act as an antidote. We reassure ourselves with the idea that all this is merely a side effect of societal development—that we do not really enjoy looking at it and instead compensate for such peripheral zones with the aesthetic beauty of our city centers or landscapes. And if we can no longer find beauty there, we go on holiday.

Dirk Eicken has been exploring for several years whether the great movements of global transformation can be named or depicted in painting. The internet acquaints us with conditions in the Global South through photos and brief texts. We learn names without having direct personal contact with the people, their living spaces, or their life circumstances—though we may well consume their products. Yacouba is the first name of a migrant from Africa who at some point began his journey toward Europe. In leaving his homeland, he left behind his social ties but retained his religion as an anchor. In his focused act of religious devotion, he creates a new space on his prayer rug, one that is separated from the physical space surrounding him. The rug seems to float on the light-colored floor. The wall behind him separates him from the local neighborhood and from his past. It radiates a warmth that only we, the viewers, can perceive. His body, bent forward and slightly turned to the right, points with his head toward an imagined center in front of the image—where we, as viewers, might stand. It points to our responsibility.

Luis Gordillo: The human sense of sight is the sensual creator of both our idea of places and of orders. It allows us to observe things side by side in their fixed simultaneity. Only through our sense of sight are we able to precisely distinguish between different places and different orders. But seeing also presupposes the awareness that we remain identical within our various perceptions—that we can place them side by side in order to compare them. But what happens when we dissolve as a self, when our perception loses its unity, its ego-center, when we split into different poles? Do we not then fundamentally lose access to the specificity of a place or an order? Gordillo’s work engages with the threats to human unity and the many forms and colors of its fragmentation.

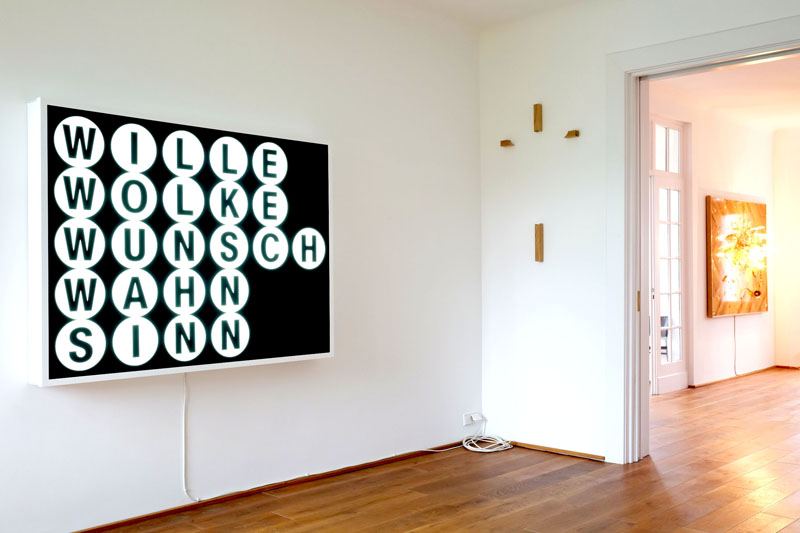

Alex Hanimann, in his artistic practice, repeatedly attempts to relate our use of language to our practices of engaging with things. He uncovers a wide variety of ordering attempts and confronts them with the attention signals of our language and its tendency toward meaningful synthesis. In doing so, he creates new orders—pseudo-orders—that expose the futility of our efforts to impose structure and that can also reveal the hollowness of our spatial arrangements. Will, Cloud, Desire, Delusion, Meaning: radiant, straight-lined Univers letters bring together terms that we can vaguely locate within ourselves—though without fixed physical place—and out there in open space. If we combine delusion and meaning, it either describes the state of a person whose relationship to their environment is disturbed because they believe in something that doesn’t exist, or the general state of a society that has lost touch with the natural world, that no longer manages to cope with reality.

Susanne Kutter prefers film as the medium for her artistic work. She is interested in the process of destruction as a successive unfolding into many smaller processes. In many cases of destruction, something is not completely erased, but small or progressively stronger deformations wear something down until its wholeness breaks into new individual parts. In the two exhibited works, we are confronted with the result of such destruction. The beautiful free fall culminates in the final jolt of impact, which releases the original order into an unpredictable recomposition of whole and parts. The resulting apparent disorder allows us, through the diverse expressive forms of the new fragments, to sense the richness of the energy unleashed in the impact. Yet Kutter doesn’t let gravity act downward toward the floor—but instead toward the wall, which becomes a new base, toward which everything has solidified. The liberating energy of gravity is now frozen in a new, glassy, frostbitten world that appears submerged beneath a water surface.

Axel Lieber repeatedly searches in his works for the tipping point—where something still appears to be what it is and simultaneously no longer does. A long piece of square-cut oak is a rod. Four square rods are nothing more than four square rods. But if these rods are positioned in a certain geometric arrangement—are they still merely four square rods? Do the four rods have to meet at right angles to form a cross, or is a fragmentary right-angled arrangement already enough? The square rods have rounded inner edges where they face each other. Was something cut away? Is this a cross without Christ? Has Christ been removed? Does Lieber’s sculpture represent a disgrace, an offense to Christianity? Does it desecrate a religious symbol? When is the arrangement of square rods a real cross, when is it a fiction of a cross, when the fiction of a removed Christ? Is a mass-produced, industrially manufactured cross even legitimately a religious symbol? We don’t know what Christ looked like—we don’t know what kind of body he had. Is the visualization of a religious idea a task of art—to shape a piece of matter, of wood, into something that allows us to see a body capable of feeling, and that brings the endurance of great suffering closer to us as a display? Does Lieber’s sculpture answer that? Is a piece of wood without Christ just a piece of wood? Can the meaning of an object be dislocated?

Christopher Muller’s work deals with the intrusion of the foreign into one’s domestic space—or with being pressured by or confronted with foreign places or orders in which one’s own system of values is turned upside down. In the case of Aleppo, this refers to the complete destruction of human living space in a civil war; in the case of Trump, to the abandonment of traditional political decorum in dealing with political opponents, the questioning and dissolution of relationships with former political partners, and the novel rejection of media oversight and judgment regarding one’s own political actions. The television or print media bring these forms of destruction directly into our living spaces—into our homes—and establish themselves there. Both watercolor works were created as part of Muller’s ongoing project to examine his immediate surroundings, aiming to act like a seismograph that registers the tremors shaking our world beyond its seemingly calm and private localities. (Full TV caption: Donald Trump: “Hillary Clinton lacks the mental and physical stamina to defeat so-called Islamic State.”)

Björn Siebert’s photograph is a remake—that is, a large-format photo of a situation the artist staged himself, recreating the scene from an image he found online. He could not determine the original location or the year the original image was taken. The motif likely traces back to Celtic practices of creating wishing trees, and may have originated in Ireland or Scotland. Personal items are attached to these trees as part of individual rituals. The content of the wish bears no connection to the location of the tree or the life setting of the person making the wish. These trees gather the most diverse wishes and individuals. The objects assembled as stand-ins for the wishes are equally varied. And it is likely that not all objects on the tree actually represent a wish—some may have been added based on various decorative ideas. For some, the wishing tree serves as a ritualized act of remembrance, a votive offering, or a consecrated site of a personal belief that remains undisclosed. For others, it may appear as a dumping ground. Both interpretations reflect the fact that an open un-order has been imposed upon the original order of nature.

Markus Willeke, in his fluid painting, has developed a special sensitivity for capturing the fleeting and the vanishing of the moment. Our world is made up less and less of stable objects and structures that remain constant in their place. Not only mobility, but also the general transformation of conditions is increasing. We populate our universe with ever more events that have hardly any lasting presence in our reality—events designed for rapid transience and that remain only as intense impressions in our memory. This can lead to a situation in which reality itself becomes invisible, and only a fleeting image carries its vividness for us: virtuality becomes more powerful than reality, the non-existent—an inverted mirror image—more striking than the real person in a real place.

Installation Views