Björn Siebert

14 March – 22 April, 2016

The exhibition takes its title, The Things We Carry 1969–1971, from a song by the group Dakota Suite. Additionally, the title is nearly identical to that of the famous Vietnam War book by Tim O’Brien, The Things They Carried, in which he refers to the many personal, unimaginable items that soldiers carried with them at the time. Both “things” and “carrying” can be understood in several ways: it may refer to what we wear or what surrounds us, but also to our memories or thoughts. What we carry can protect us, highlight us, connect us, burden us, or even distort us. Memories or thoughts are shaped by personal experiences as well as by media storage, which we appropriate in the form of writing and images. Here, photography plays a major role. At first, it seems easy to read, but upon closer inspection, it too is wrapped in media forms. We must develop practices to interpret the changing forms of the medium for ourselves.

However, Björn Siebert is not only concerned with the obvious results of the medium of photography, where reality is depicted or captured in images, but also with its counterpart—reality itself. This may seem paradoxical at first, since photography is reputed to merely mechanically reproduce reality in images. But instead of capturing reality, Siebert constructs his pictorial reality detail by detail. He is interested in the fact that not only individual objects, but also reality itself, is constructed—that the environment of objects in the form of city, landscape, portrait, or interior results from processes of construction. Since we overlay our reality with cultural connotations, we can then ask how these connotations, in turn, influence the representations of this reality and their reception, thereby affecting the aesthetics and legibility of each image.

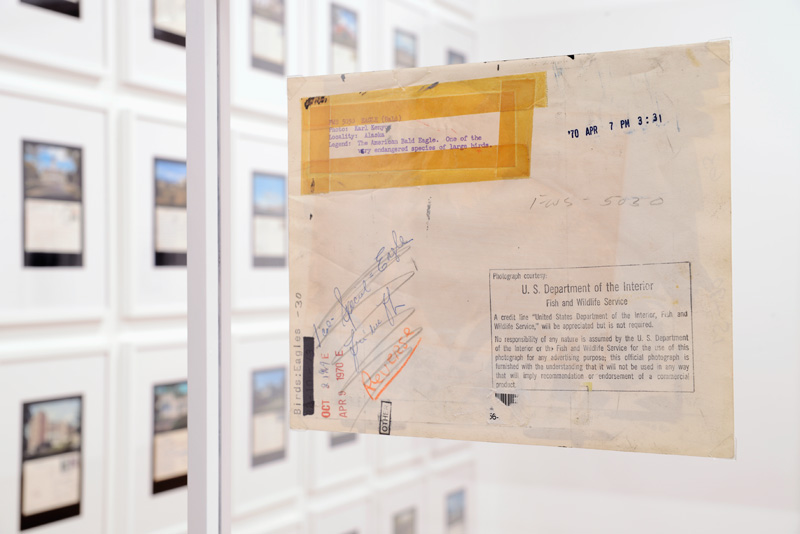

Because Siebert is interested in reality as something produced, represented, and perceived, he begins with found material in which reality has already taken on a particular representational form. He acts as an archaeologist, unearthing evidence of representation. For the exhibition, Siebert combed through the enormous archive of images commissioned by the U.S. Congress from photographers to document the country during the years 1969–71. From such archival images, one might expect the documentation of well-known buildings as well as an overview of public space. During his research, Siebert came across not only images of representative buildings, but also photographs whose purpose and significance are not immediately clear, prompting one to wonder why they were taken at all. He is guided by the idea that the seemingly incidental all the more subtly contains implicit intentions. It is at this point that Siebert becomes a visual analyst. He selected images that reveal mentalities behind the production of realities. Since these are photographs of architecture, Siebert asked himself how these images reveal mentalities in the handling of materials and structures, and how spaces present themselves in terms of their accessibility between inside and outside—how, in the paradoxical combination of elements, these mentalities express themselves. For instance, he found images of interiors that also display pictures of the exterior on their walls. The splendor and picturesque quality of the outside contrasts with the accumulation of disparate parts, with the gesture of adding and combining the diverse within the interior.

In a next step, Siebert takes on the role of curator—assembling a selection of images and placing their interrelations into a state of visual tension. Then he makes his artistic decisions regarding the material treatment of the images and their presentation mode: what new material quality and size should the images take on? For the source material from the U.S. Congress, Siebert chose digital screen printing on Kappa board. In this production method, the halftone raster remains visible, and there is neither pure white nor deep black. The images gain a silvery shimmer, placing them visually close to newspaper photographs. Since the images are architectural photographs, their physical appearance as newsprint images evokes the expectation of events—but no overt events appear in them. Instead, what surfaces are backgrounded actions—the ways in which disparate parts were combined.

In addition to the archive of the U.S. Congress, Siebert tapped into other sources: image archives from the internet, newspaper archives such as that of the Baltimore Times, and even postcards. The postcards form a large independent body of work. Each postcard is shown on both sides: the color front was scanned, exposed as a C-print, and framed together with its original handwritten reverse side. All postcards date from the year 1969—the year of the moon landing, as the culmination of humanity’s longing to reach into space, and America’s answer to the Tet Offensive with napalm bombs—systematic, anonymous destruction of people and landscape. The postcards show the additive nature of individual buildings assembled within American cities. There are no iconic tourist landmarks. They are not tailored to a vacationer’s gaze. These images express how, in the 1960s, existing and newly constructed architecture was visually presented through the additive gesture of assembling elements and through their accessibility to public space.

When combined with the personal text on the back, the result is a mixture of private daily life and public marking and structuring of the world in a specific cultural moment.

At the center of his exhibition, Siebert placed a photograph originally taken by the renowned American photographer Walker Evans, showing the front door of his equally famous colleague Robert Frank. Siebert meticulously analyzed this photographic situation, reconstructed it detail by detail, and then captured it anew in a large-format photograph. The original photograph is dated between 1969 and 1971. For Björn Siebert, it gains a symbolic charge, as it was taken precisely at the end of the socially and artistically experimental era of the 1960s—a time that led to a redefinition of public space. The image shows an open front door through which bright light enters, viewed from inside a house constructed entirely of assembled wooden elements. The interior lies mostly in darkness, with only silhouettes of individual objects visible; nothing of the exterior is discernible.

The spatial situation is difficult to grasp—what dominates the lighting is a deep black with a few highlights, contrasted by the brightness outside. This creates a magical moment of transition: from a space of human life filled with man-made objects that, in their details, do not reveal a clear narrative of life—toward a brightness beyond, which is likewise inaccessible.

If one reads the darkness as the past and the brightness as the future, an open question remains: how do these two unfold in relation to each other? How does the personal space of darkness, of the constructed, the private, merge with the bright space of the public or the conceptual? Will the public sphere of the future be excluded from this private space? And what kind of relationship between past and future might emerge from this?

Although Walker Evans used a tripod for his photograph at the time, the perspectival lines are not exactly vertical or horizontal. Siebert draws attention to this wavering, indeterminate quality as a defining character of the photo by presenting two variations of the original image, in which he has altered the spatial edges and the camera’s visual access to the door almost imperceptibly.

In this pictorial reinterpretation, Walker Evans’s original photograph—with its stark black-and-white modulation and a door that opens to nowhere—becomes a metaphor for the temporal watershed between the 1960s and 1970s: the end of a redefinition of public space that had consisted in opening it up to private needs and manifesting this openness through architectural accessibility and modularity. At the same time, the image serves as a plea for the magic of a picture in which the visible and invisible intertwine so intimately that even its discernible meanings resist arriving at a definitive interpretation.

Installation Views

Fotos: Björn Siebert