ALEX HANIMANN

AUGUST 27 – OCTOBER 22, 2023

If one were to categorize the broad oeuvre of Alex Hanimann within a specific genre, he would be best described as a draughtsman. Drawings capture reality in aspects that can be expressed through points, lines, or systems of lines, but they only partially capture the real. Many would argue that photographic images represent a much richer or denser access, that they are far superior to drawings. However, Hanimann’s artistic work teaches us that this is not the case. He also engages intensively with photographic images. For these too, it is evident that there is no seemingly direct capture from reality; they too must be interpreted, and their visual properties must be linked with conceptual ones to arrive at an interpretation of the depicted.

The visual properties of a photograph may seem at first glance to be different from points or lines. On closer examination, however, it becomes clear that these properties should only be seen as another type of density of points.

Hanimann’s works observe different penetrations of reality as expressed in media images and texts. Rarely is only one thing depicted or expressed; instead, side aspects gather, and everything can be reversed depending on how the image or text cut is made, so that from the beginning there is a noise of side or interfering noises.

Texts appear much simpler than images, consisting merely of a sequence of words. There is a fixed order. However, in his word drawings, Hanimann observes that this order can quickly become confused, that just one slightly inappropriate word can cause disturbances in meaning. With our words, we try – like fishermen casting nets – to capture different aspects of the world. We find that the nets often gather things that do not really belong together and which we were not trying to capture. Success or failure are not always predictable: profundity and platitude reside together in the depths of the sea of interconnected meanings.

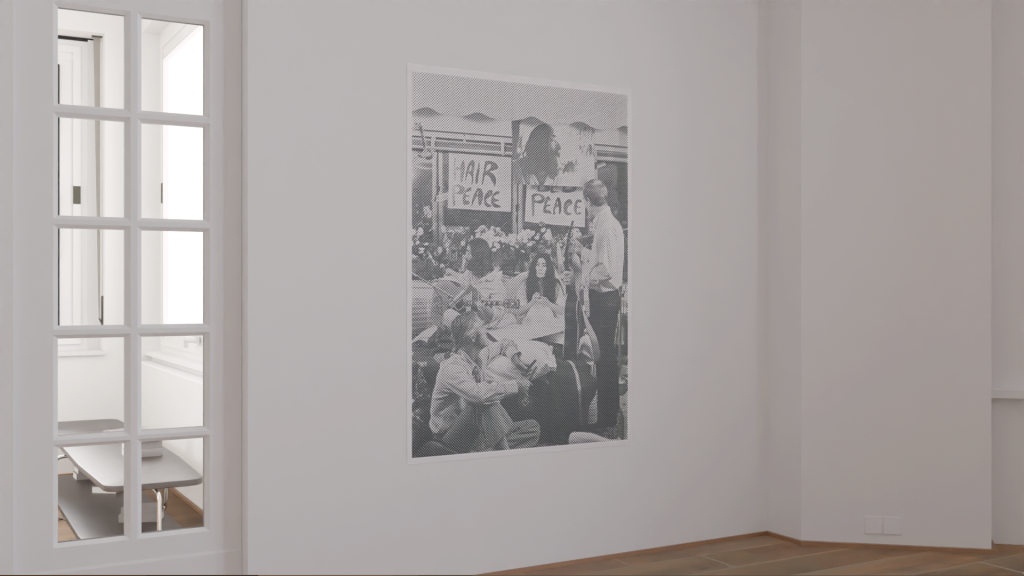

For his engagement with media images, Hanimann has compiled an extensive image archive from newspaper, book, and film still sources, gathering a variety of oddities. Often, such media images aim to document a state, an event, or an atmosphere. What they capture, however, is far more than just that one event. In images, attitudes and cultural settings sediment through the implicit habits of staging. These can be made visible through image editing steps, by gradually filtering and changing the density of the enclosed information. This results in holes, peculiar missing spots, unbearable emphases, and other distortions. For media images are composed of elements that can be interpreted both figuratively and abstractly. When the formal basis of the images, their rasterization for printing, their composition of varying clusters of dots in different densities is made apparent, the weights of the dual-track interpretation shift. If you reduce or intensify the dots, alter the hard edges and corners, then the representational interpretation tips, and suddenly we speak of an overflowing or encroaching darkness, of a white emptiness, of formlessness, mushy expansions, swelling and receding color streams, of latent patterns. The penetrations of reality become a thicket or a pictorial desert. Particularly paradoxical here is that our experience in dealing with images is subverted: if we want to see something more clearly, we look at an image up close. However, in a raster-manipulated image, any overview and control over the image is lost at close range, and only from a distance do we regain reduced representational readings.

Since Hanimann is interested in the pitfalls or the fate of meaning in our social communication, he becomes a master of ceremonies for meaning in his image manipulations. How is meaning constituted, how can meaning be lost, dissolve into half-sense or nonsense? How do hands, arms, legs, or various body postures and rotations fit together in the different densities of our social spaces and social encounters, how do such body movements become gestures of turning towards or away from others? How does the accumulation of human movements become an interpretable context of action, a cooperation of various forces? How can we read both sense and nonsense from images when we cannot find instructions for connections among their different elements? While we try to emphasize the meaning of images through verbal descriptions, paradoxically, it is often the nonsensical in images that is particularly remembered.

Images are embedded in our social media memory. Each individual is, depending on age, particularly interested in the atmosphere of certain images because they signal a cultural upheaval, a generational marker, and stores them unconsciously. However, part of the information is lost over the years. We only remember fragments of what we originally saw. Such a loss can be paralleled with the loss of information in pictorial interventions.

Hanimann explores this constant shifting of the traditional and the remembered densities, this complex structure of meaning, memory, and nonsense in his image constructions. Through these investigations, he challenges our conventional understanding of images and their role in the construction of social reality.

Rolf Hengesbach