Olga Stozhar

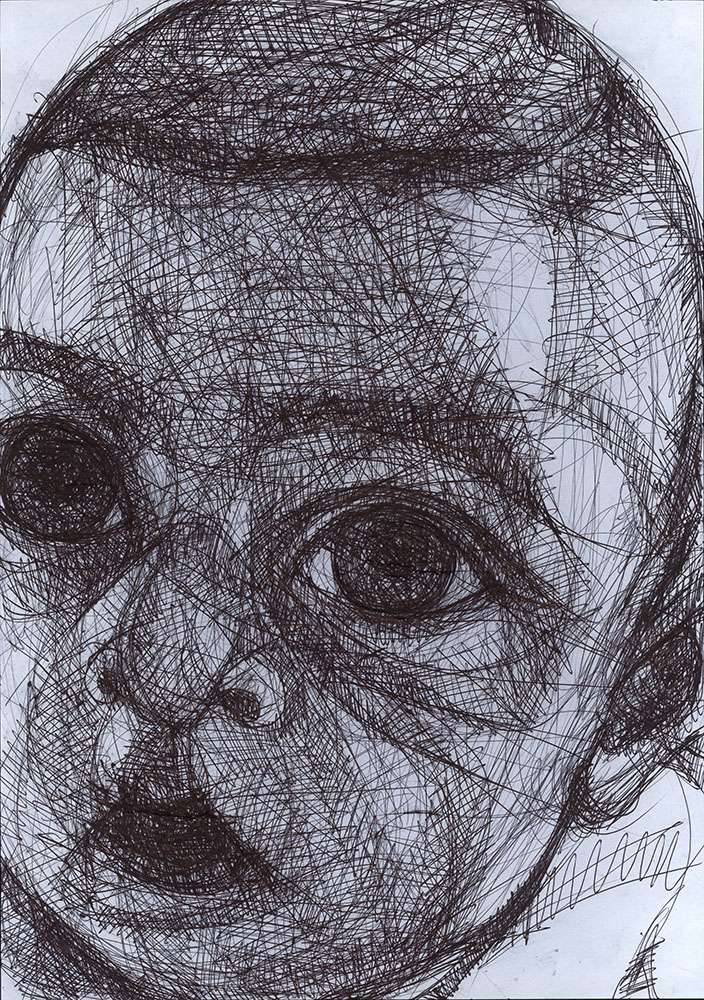

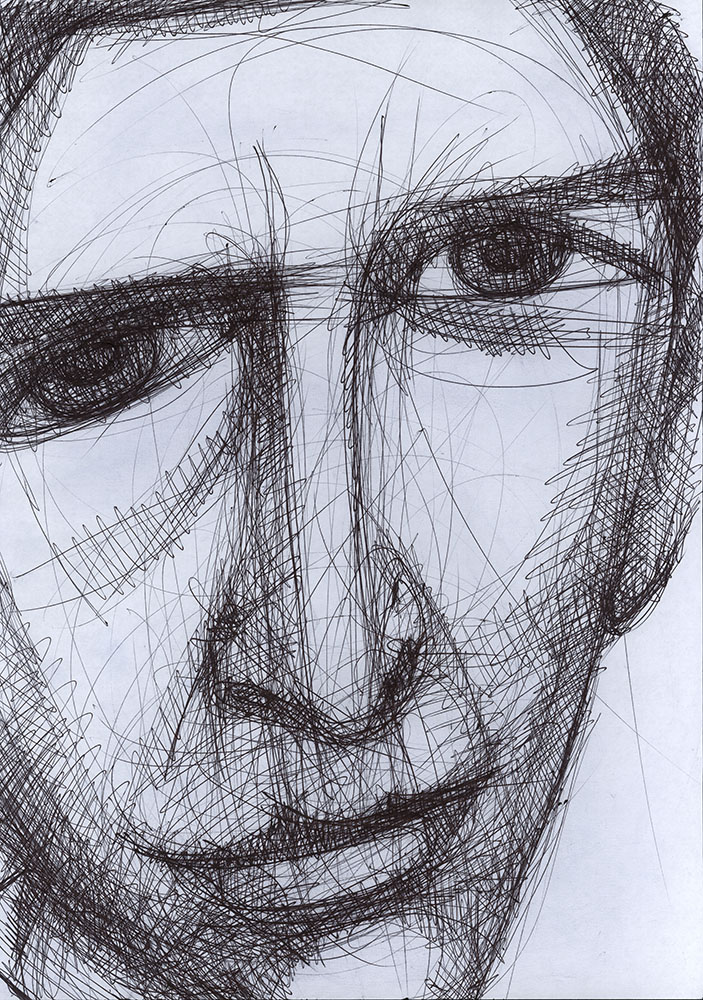

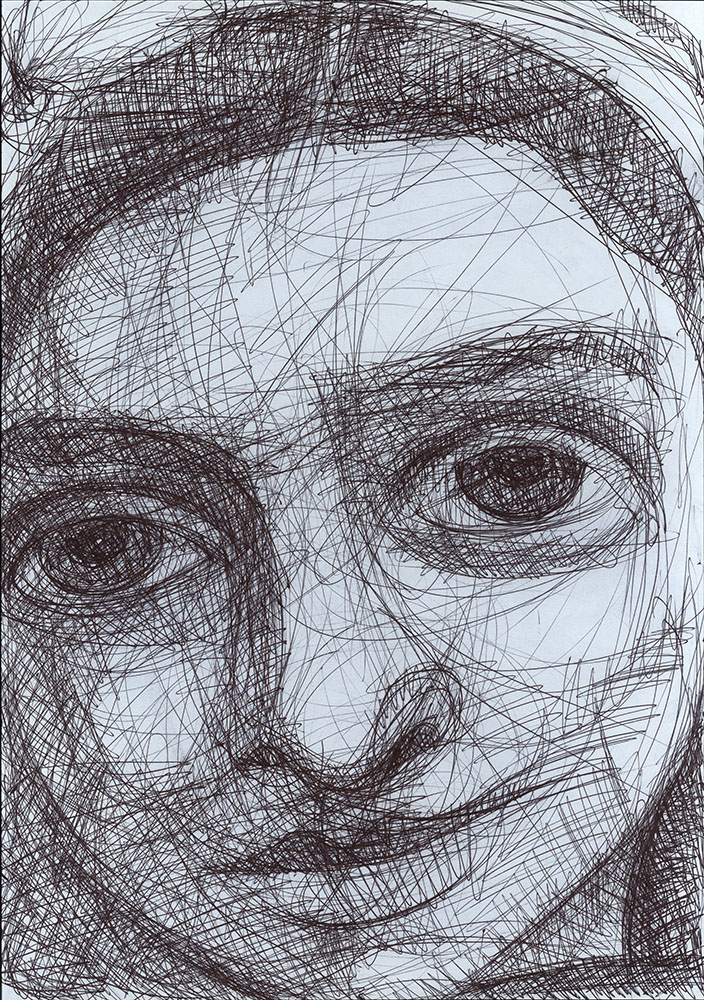

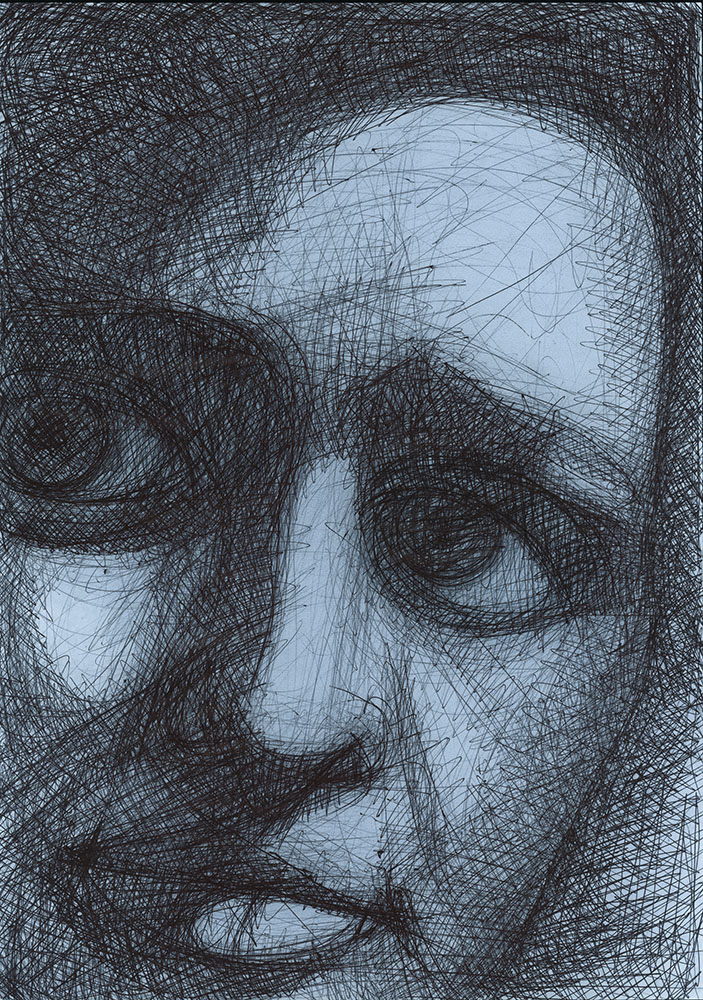

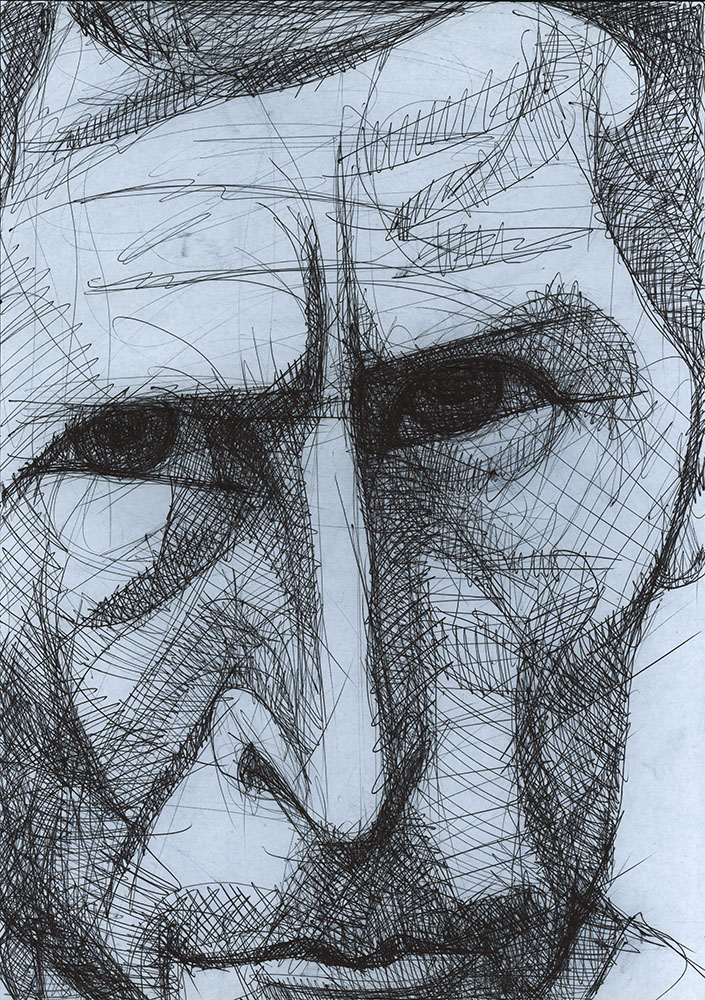

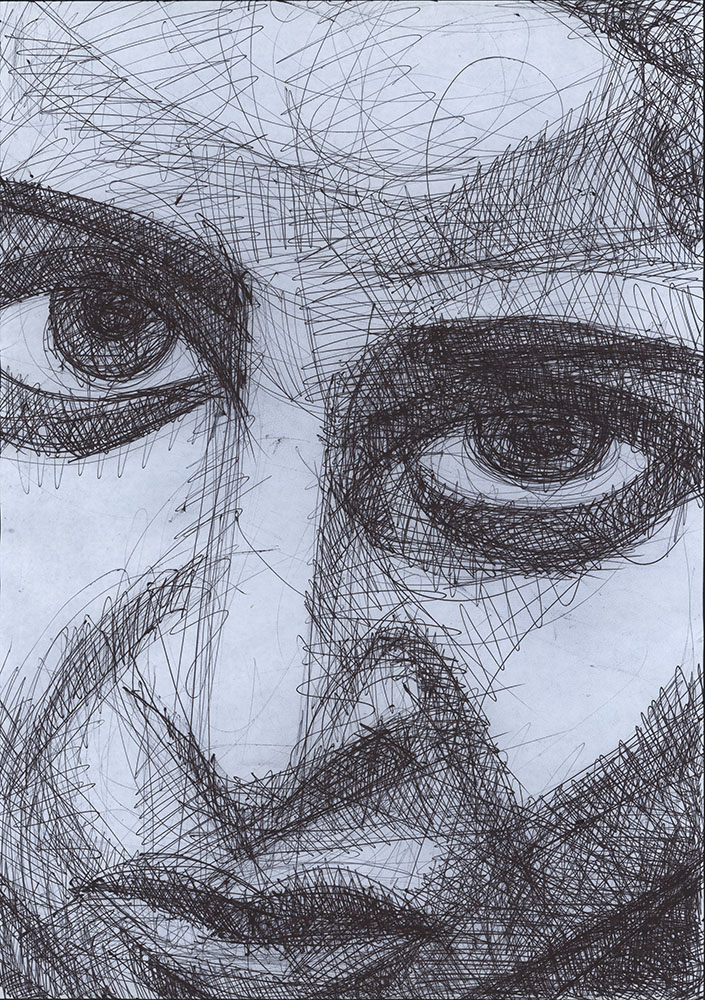

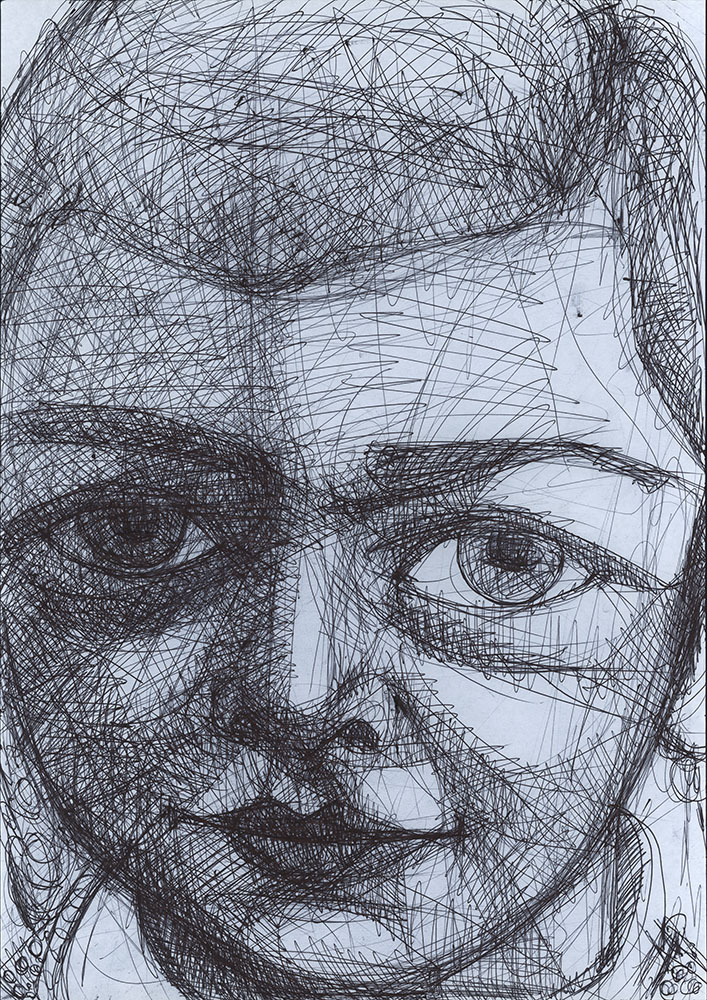

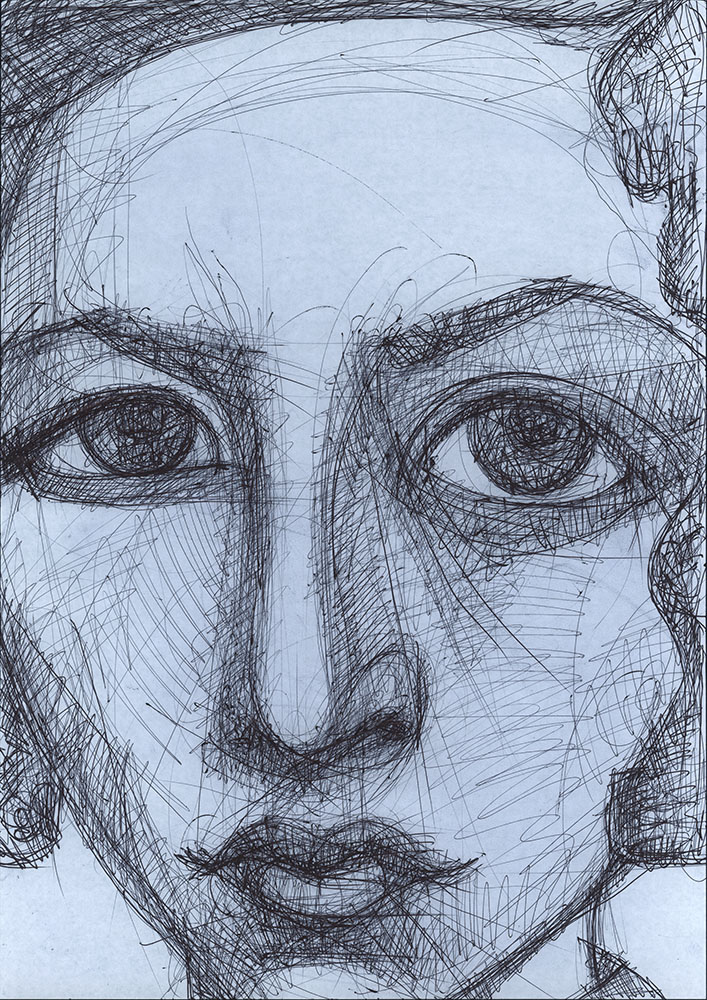

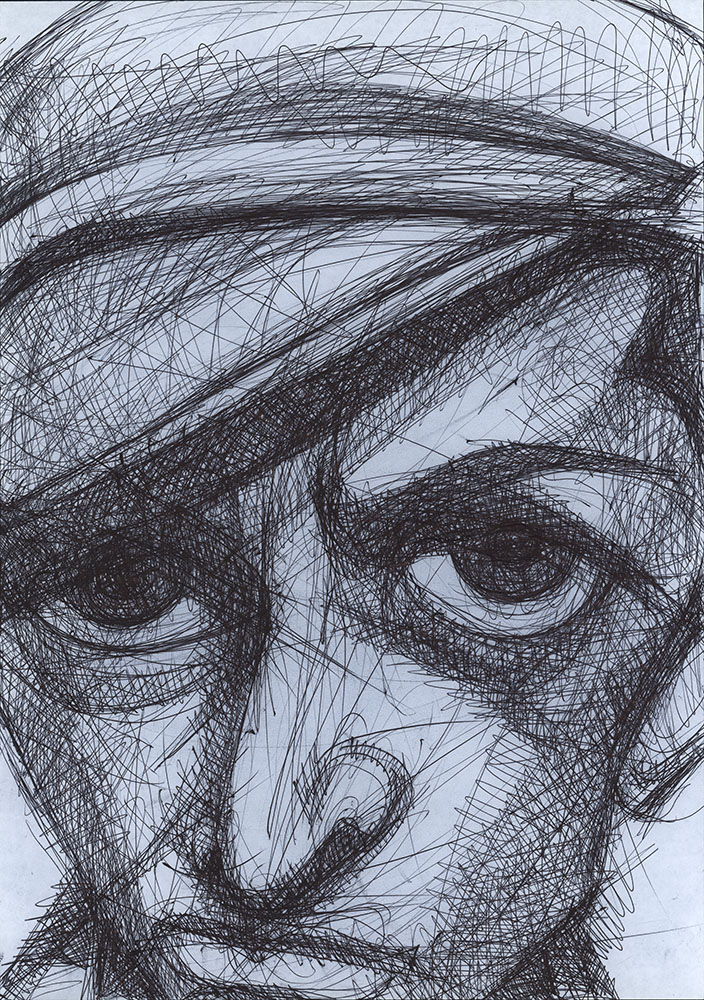

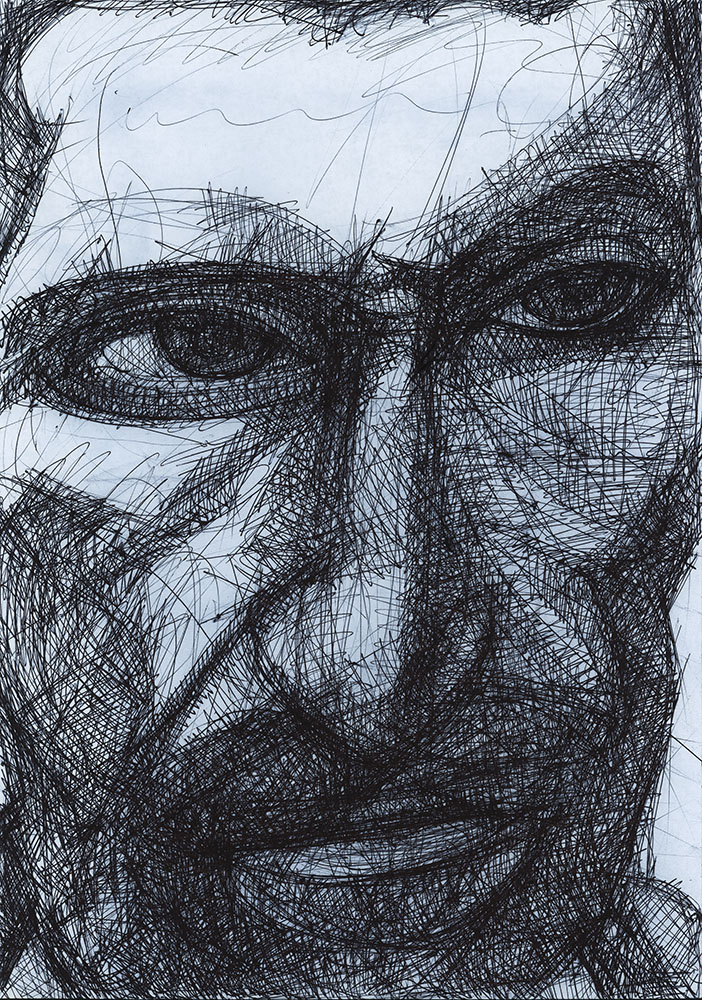

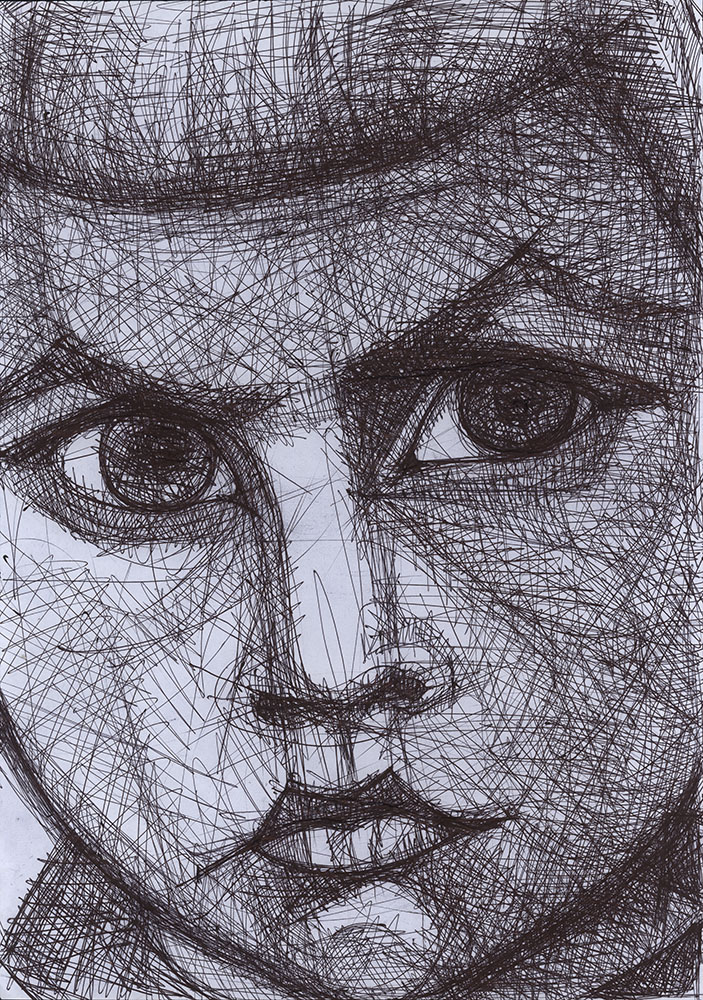

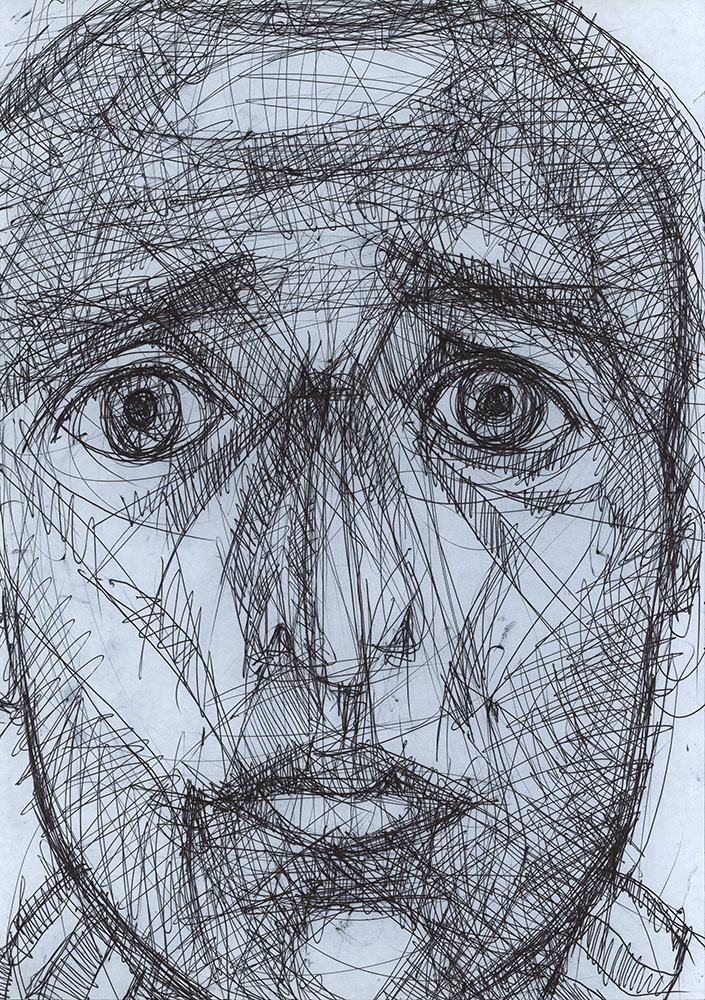

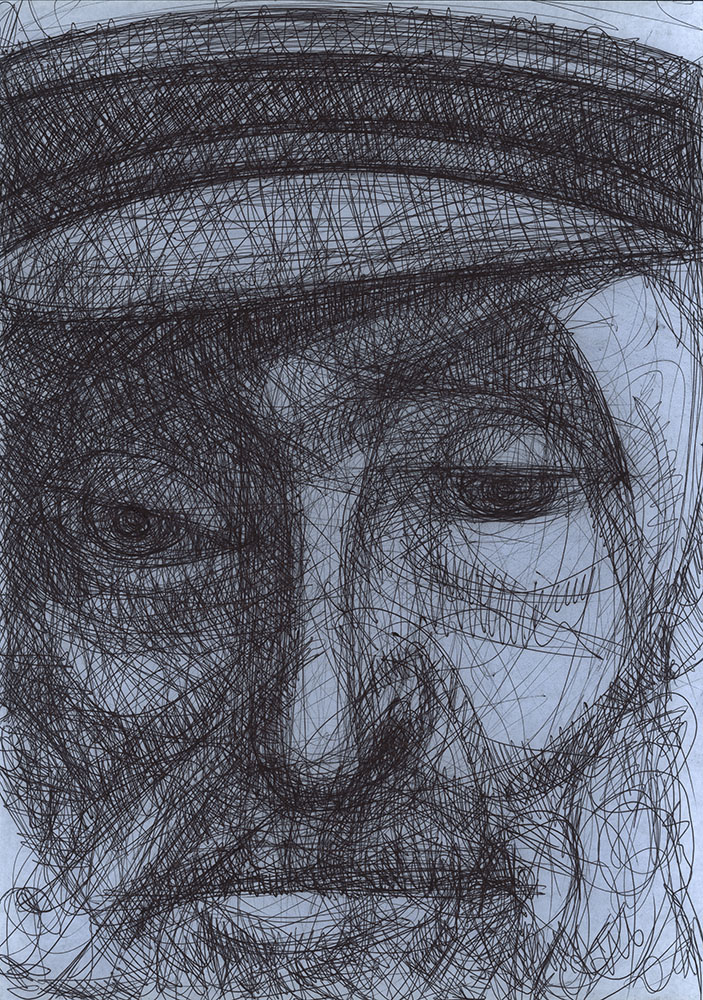

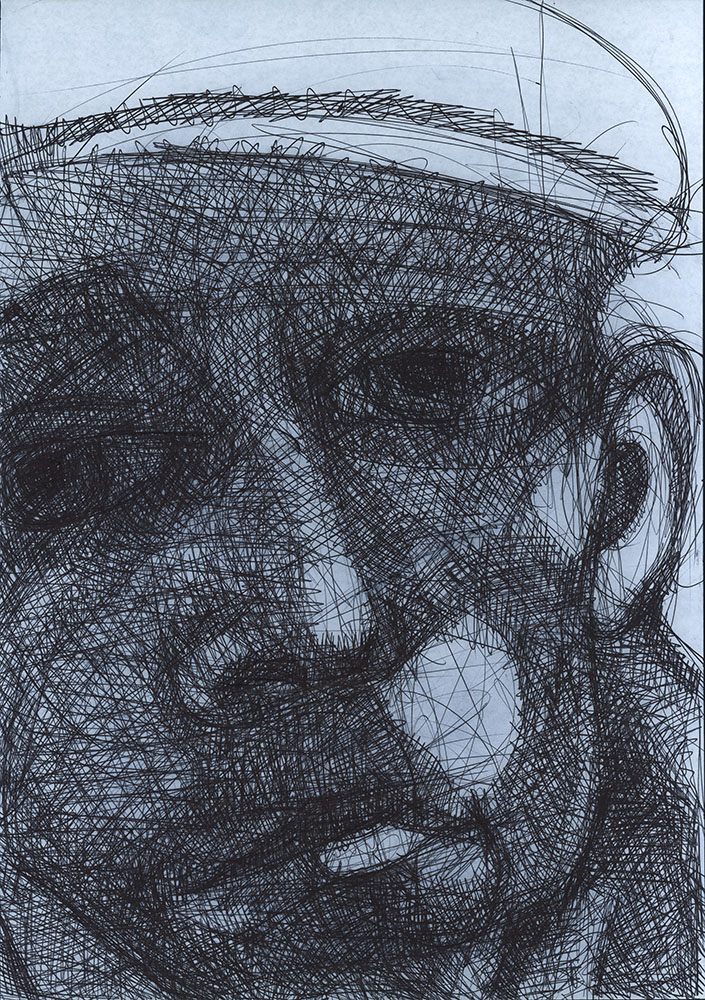

For many years, the Jewish Russian artist Olga Stozhar has been working on a large-scale project aimed at addressing a subjective history of remembrance and artistically “reviving” the victims of National Socialism. The project is titled: they are looking at us. For this, Olga Stozhar uses photos of victims who perished in concentration camps or during the Warsaw Ghetto uprising. She accesses these photos through archives and available documentation. She uses them as templates for a highly intensive drawing process in which she brings the facial features of the victims to life on A3-sized paper, using a continuous sequence of strokes in black, blue, or red.

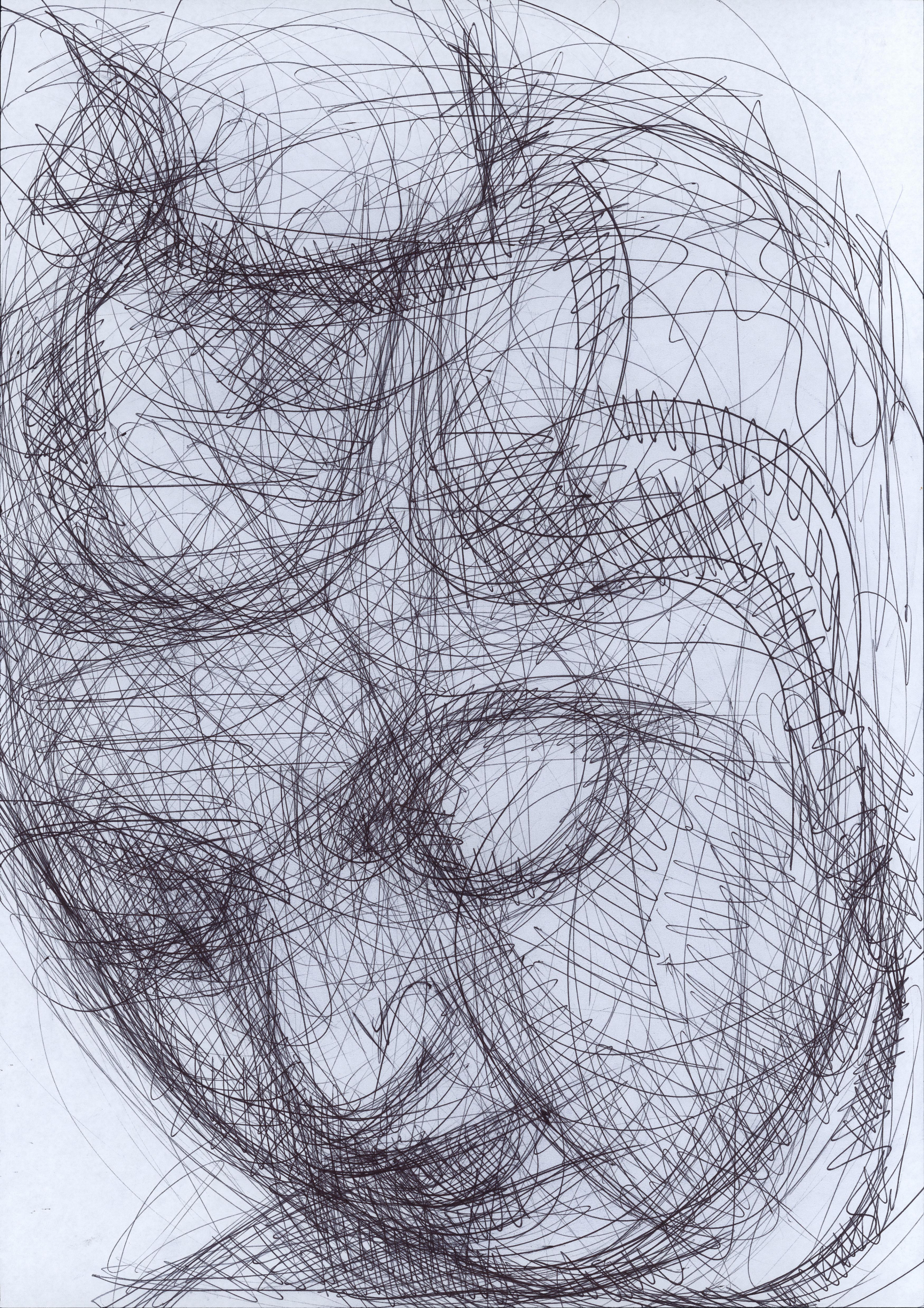

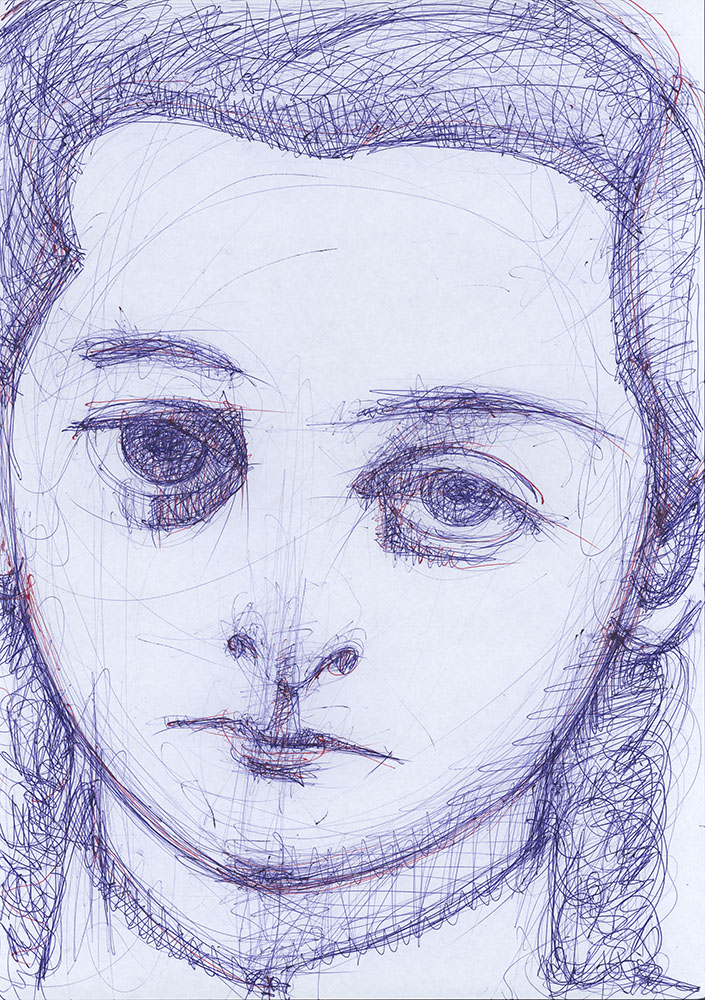

The vividness of these portraits stems largely from the artist’s electrifying, dynamic linework. In her approach, she diverges from classical analytical drawing techniques. Rather than using lines primarily to outline volume and accentuate a face’s characteristic features, she employs the line like a pendulum with a weight, using broad, sweeping motions to trace an extremely complex path across the surface of the paper. This leads her repeatedly to the edges of the sheet and back again into various zones of density that emerge throughout the process. Her drawing evokes the early scribbles of young children—where it’s still unclear whether the drawing depicts anything at all or if the child is simply exploring its own movement. This return to the origin of graphic expression gives her drawings something elemental: a simultaneous discovery of the self and an empathic connection to the other and their emotional state. In this sense, one can say that Stozhar’s drawing instrument is a direct extension of her own emotions in relation to the murdered other. At the same time, her work reflects a lineage connected to Russian Primitivism and Constructivism.

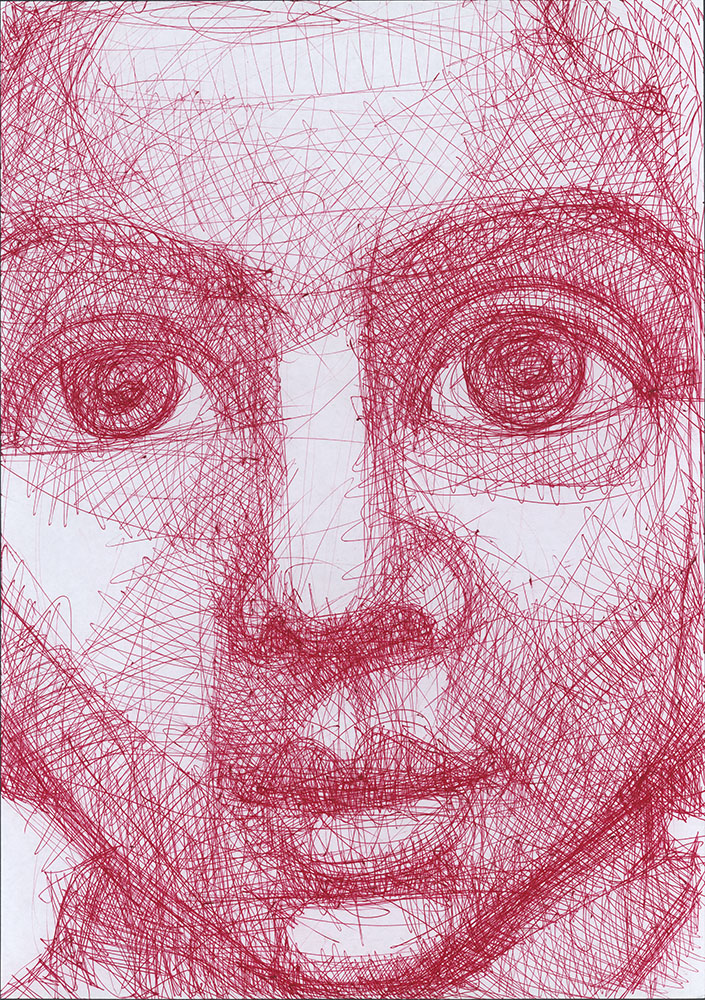

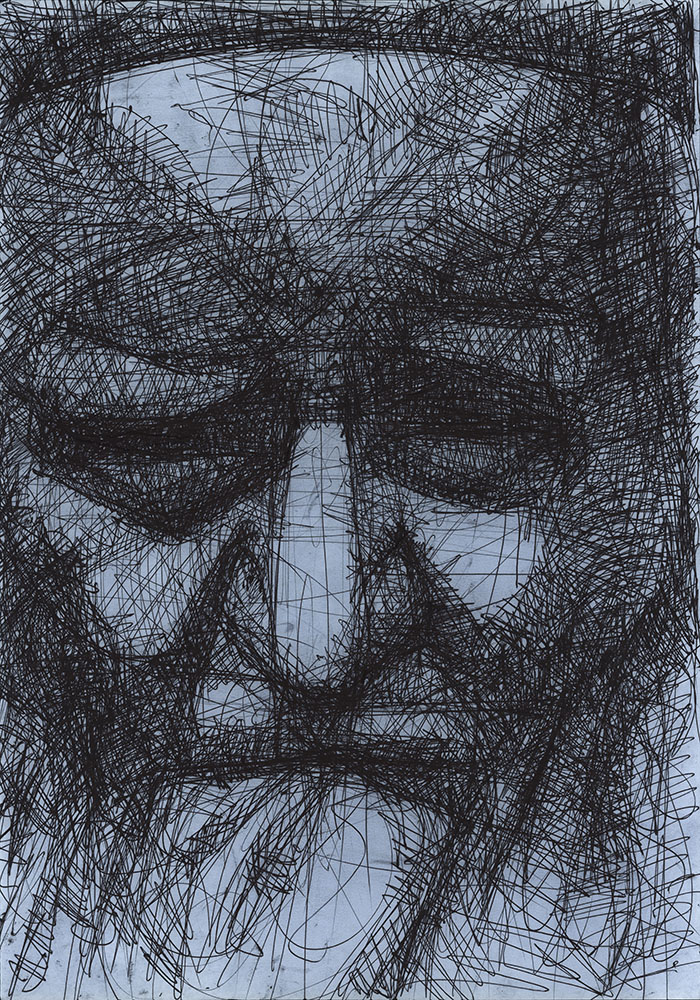

Stozhar uses a fine, circling line. This line always remains a line. Even in the most intense densifications and erratically jagged forms, it is the single line that traces a path toward an unforeseeable end. Sometimes pressed more forcefully, sometimes more gently onto the paper, the lines always remain thin. She does not employ multiplied or mechanical lines in the form of hatching. Her line shows densification, entanglement, a dense self-intertwining—but also isolation within the empty space. Its path across the paper is marked by dynamic progression and expansion, and at the same time by countless reversals. Each drawing explores the space of the paper differently. Sometimes, areas are so densely filled with lines that the white of the paper disappears; other areas remain open, with the white paper clearly visible. However, the white and the black have nothing to do with light and shadow. Remarkably, in Olga Stozhar’s world of drawing, there is no light and no shadow. One could therefore also speak of a world alongside our natural one—a world of speaking spirits or of souls. But it is not a dead world, nor a transcendent heavenly realm; rather, it is one of aliveness. In this world, however, nothing is narrated; instead, everything is concentrated on elemental human expression.

The faces are rendered at a scale much larger than a human face. Yet they do not appear monumental. The focus on the harmony of lines reveals purely the human expression, not the individual features of the face. This concentration on expression keeps us at a distance, so that we perceive the faces as equals, not as enlarged. The clearly visible physicality and energy of the line—alongside the fragile delicacy and thinness of the paper—makes human vulnerability and emotional impression all the more apparent.

Each face is positioned differently within the image format, with Stozhar defying gravity and ignoring the vertical and horizontal orientation. Sometimes faces are tilted so much that parts are cut off. This, however, enhances the immediacy and directness of the encounter, as though the face emerges from a living moment.

The dialogue between dense areas of linework and the blank white surface of the paper leads to a constant perceptual shift in the viewer. One cannot decide whether the true weight of meaning lies in the fullness or in the emptiness. It is precisely this oscillation that gives Stozhar’s approach its appropriateness in the open assignment of meaning—since we must work our way into each drawing differently, just as we would with any promising new acquaintance.

When viewed sequentially, like in a book, the richness and variety of the human face—with all the life possibilities inscribed in it—comes to light. When the faces are then seen carefully arranged in groups within the exhibition, another paradoxical experience arises. In the fullness of their harmony, the loss humanity has suffered through these murders becomes apparent. At the same time, and this is a remarkable experience, a relationship develops between these people—they begin to speak to one another.

Because dialogue plays such an essential role in these grouped presentations, Olga Stozhar spent a long time working on the installation. Her goal is to show warmth and love—the opposite of violence and death, cruelty and injustice.

As a dialogical network structure, Olga Stozhar chose a rhythm of three, which automatically creates a tension between centralization and decentralization, between the middle element and the outer ones. At the same time, the consistent spacing creates vertical and horizontal connections between the faces. From this, a more complex field of possibilities emerges, as formal characteristics from one drawing can leap to the next. Each face is shaped by the rendering of the mouth, nose, eyes, and ears, as well as the hair that accompanies them. How eyes relate to one another, how a nose positions itself between them and moves toward a mouth, how the mouth assigns the nasal cavities a form of closure or openness through the curve of the lips—all of this happens differently each time. But since Olga Stozhar’s line never describes a single sensory organ in isolation, but rather embeds it into a web of connecting lines from which it emerges, these connecting lines can also begin a conversation with a neighboring face. Material aspects like hair or individual forms are not imitated—everything is oriented toward connection. However, the paths of connection can vary greatly in their formal execution.

One organ, however, stands out despite the restlessness of the line and forms a place of stillness within the dynamic accents on the surface: the eyes. They are a fixed point, fastening themselves to us as viewers and demanding an answer from us to the open questions of humanity.

Can art deal with this catastrophe of humanity? Adorno’s dictum still looms: that to write a poem after the horrors of Auschwitz would be barbaric. This dictum cannot be answered with artistic realism: the murdered cannot be brought back to life through depiction. Olga Stozhar’s response to this challenge is twofold: in place of realism, she employs a drawing process that is not directed at outward appearance, and she omits the horror itself. Instead, she begins at the core of humanity—individual expression. Her act of reanimation remains entirely tied to the artistic process.

Stozhar creates for herself the free line, which seems to stream out from within her and carve a path in a dynamic immersion into the Other. The line is set into an open process, one that must be different for every person, every time. Stozhar has not devised a fixed strategy, but instead continually engages in an open search for the Other. In an apparently erratic process, she allows her line free rein. At times, she darkens the white space of the drawing sheet to such an extent that she pushes the paper to the brink of its own fibrous limits. The unfamiliar person is created through the drawing process, not from any specific details—everything is aimed at revealing the complexity of the individual, which emerges through the connections, the interplay of density and emptiness, and their interactive dynamic.

Olga Stozhar’s approach deliberately avoids a comprehensive depiction of the victims’ suffering. Instead, she establishes a new connection between them. Her delicate, dynamic, and fine line allows the faces to speak in such different ways that a sense of humanity emerges between them—one that was utterly absent in the perpetrators. Stozhar’s formal device—the unrestrained drawing pencil—sets a dialectic in motion that liberates the victims in their individuality, condenses this individuality into a polyphonic chorus of unique voices, and thus creates a sense of togetherness which, in paradoxical fashion, celebrates human diversity in the face of their destruction and confronts us, the later generations, with the question of humanity.

Works

A selection from the project: They are Looking at Us, 2017/23

Biography

1966 born in St. Petersburg (RU)

1987–1990 Art studies at the Imperial Academy of Arts, St. Petersburg (RU)

2000–2004 Work on the project “Deep Purple in Art,” approx. 100 paintings on canvas

2004–2007 Work on the project “Rolling Stones in Art,” approx. 100 paintings on canvas

2008–2015 Work on the project “AC/DC in Art,” approx. 100 paintings on canvas

Since 2017, work on the project “They are Looking at Us”; approximately 4,500 portrait drawings of Holocaust victims completed so far.

Since 2022, work on the project “Le Grand Cinema”

1999 Publication of the art catalog “Olga Stozhar. Works 1996–1999”, Berlin

2004 Publication of the book “Deep Purple in Art”, Edition Braus, Heidelberg / Berlin

2007 Publication of the book “Rolling Stones in Art”, Edition Braus, Heidelberg / Berlin

Lives and works in Berlin, Tel Aviv, and St. Petersburg.

Awards / Scholarships

1997 – 1999 Stipendium der Karl-Hofer-Gesellschaft, Berlin

Solo-Exhibitions

2020 „They are Looking at Us“, Hengesbach Gallery, Wuppertal (D)

2008 Gallery Sandmann, Berlin (D)

2007 Gallery U7, Frankfurt/M (D)

2004 Kunst-Stiftung Starke, Löwenpalais, Berlin (D)

2003 Gallery Bernauer, Frankfurt/M (D); Central Exhibition Hall “Manege”, St. Petersburg (RU)

2002 Gallery Heitsch, München (D); Gallery Nieppel bei Morawitz, Düsseldorf (D); Gallery Mainz, Berlin (D); Gallery Dürr, München (D)

2001 Central Exhibition Hall “Manege”, St. Petersburg (RU); Gallery “Weber”, Wiesbaden (D)

2000 Gallery Wild, Frankfurt/M (D); Gallery Haasner, Wiesbaden (D); Gallery Mainz, Berlin (D)

1999 Gallery Hesselbach, Berlin (D); State Museum of Urban Sculpture, St. Petersburg (RU); Art Frankfurt Gallery Wild (D)

1998 Gallery Wild, Frankfurt/M (D); Gallery Mainz, Berlin (D)1997 Gallery Arcus, Berlin (D)

1996 Gallery Borey, St. Petersburg (RU); Gallery Haasner, Wiesbaden (D)

1995 Art Frankfurt Gallery Wild (D); Palace Belozersky-Beloselsky, St.Petersburg (RU)

1994 Gallery Wild, Frankfurt/M (D); IKB Industrial Bank, Berlin (D)

1992 Gallery Forum, St.Petersburg (RU); Marble Palace, St. Petersburg (RU); Gallery Baltic, St. Petersburg (RU)

Group-Exhibitions

2020 The State Russian Museum, Marble Palace, St. Petersburg (RU)

2016 Museum of Contemporary Art, Perm (RU)

2015 The State Russian Museum, Marble Palace, St. Petersburg (RU)

2009 Kunst-Stiftung Starke, Löwenpalais, Berlin (D)

2000 Central Exhibition Hall “Manege”, St. Petersburg (RU)

1999 The State Russian Museum, Michailov Palace, St. Petersburg (RU)

1997 Gallery Giessler und Nothelfer, Berlin (D)

1994 “New Art”, Estland (EST)

1993 Central Exhibition Hall “Manege” St. Petersburg (RU)

1990 “Diagilev Seasons”, St. Petersburg (RU)

* Catalogue

Collections

The State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg (RU), Villa Haiss Museum für Zeitgenössische Kunst, Zell am Harmersbach (D), Kunst-Stiftung Starke, Berlin (D)